Management of prolactinoma in 2025

Author:

Georgios E. Papadakis, MD

Service of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism

Lausanne University Hospital

Faculty of Biology and Medicine

University of Lausanne

Email: georgios.e.papadakis@chuv.ch

Vielen Dank für Ihr Interesse!

Einige Inhalte sind aufgrund rechtlicher Bestimmungen nur für registrierte Nutzer bzw. medizinisches Fachpersonal zugänglich.

Sie sind bereits registriert?

Loggen Sie sich mit Ihrem Universimed-Benutzerkonto ein:

Sie sind noch nicht registriert?

Registrieren Sie sich jetzt kostenlos auf universimed.com und erhalten Sie Zugang zu allen Artikeln, bewerten Sie Inhalte und speichern Sie interessante Beiträge in Ihrem persönlichen Bereich

zum späteren Lesen. Ihre Registrierung ist für alle Unversimed-Portale gültig. (inkl. allgemeineplus.at & med-Diplom.at)

The management of prolactinomas has evolved significantly inrecent years. Cabergoline remains the most frequently implemented first-line therapy due to its high efficacy and the abundance of high-quality data regarding its safety profile, likelihood of resistance, and need for long-term treatment. Conversely, surgery has emerged as a valid alternative for microprolactinomas and noninvasive macroprolactinomas, provided access to a high-volume pituitary neurosurgeon is guaranteed. As management of prolactinomas becomes more personalized, patient preferences are an increasingly important factor.

Keypoints

-

Cabergoline intolerance or resistance are relatively rare. However, most patients with prolactinoma will require long-term therapy, although favorable predictive factors for dopamine agonist withdrawal have been established.

-

Surgery by a highly-experienced neurosurgeon has emerged as a valid alternative to medical therapy in microprolactinoma and intrasellar macroprolactinoma, considering patient preference after information on benefit-risk ratio of each option.

-

Fertility should be discussed before conception, especially in women with macroprolactinoma, to ensure the best strategy for conception and to reduce risk during subsequent pregnancy.

Prolactinomas are prolactin-secreting pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNET) that originate in the lactotroph cells of the pituitary gland. They account for approximately 50% of all PitNET in both sexes. They are distinguished from other PitNET types by their unique clinical presentation and sex-dimorphic manifestations, as well as by the fact that medical therapy with dopamine agonists (DA) is the primary treatment, unlike transsphenoidal surgery (TSS) for other symptomatic PitNET. Recent data has modified our diagnostic and therapeutic approach to prolactinoma, as outlined in a 2023 consensus statement.1

Epidemiology and clinical presentation

Based on their maximal diameter, prolactinomas are classified as microprolactinomas (<10mm) or macroprolactinomas (≥10mm). Microprolactinomas predominantly affect premenopausal women (with a female-to-male ratio of 5–10:1) and rarely exhibit proliferation and subsequent growth. Conversely, prolactinomas in men are usually macroadenomas and can progress more aggressively.

Prolactin excess causes hypogonadism and infertility in both sexes. The resulting manifestations of sex steroid deficiency are often gender-specific and may include reduced libido, erectile dysfunction, and gynecomastia in men and oligomenorrhea, vaginal dryness, and galactorrhea in women. In the case of a macroadenoma, the pituitary tumor itself may exert compressive effects, leading to headaches, visual disturbances, and hypopituitarism. Although prolactinomas are associated with an increased prevalence of obesity, this link appears to be primarily mediated by underlying hypogonadism.2

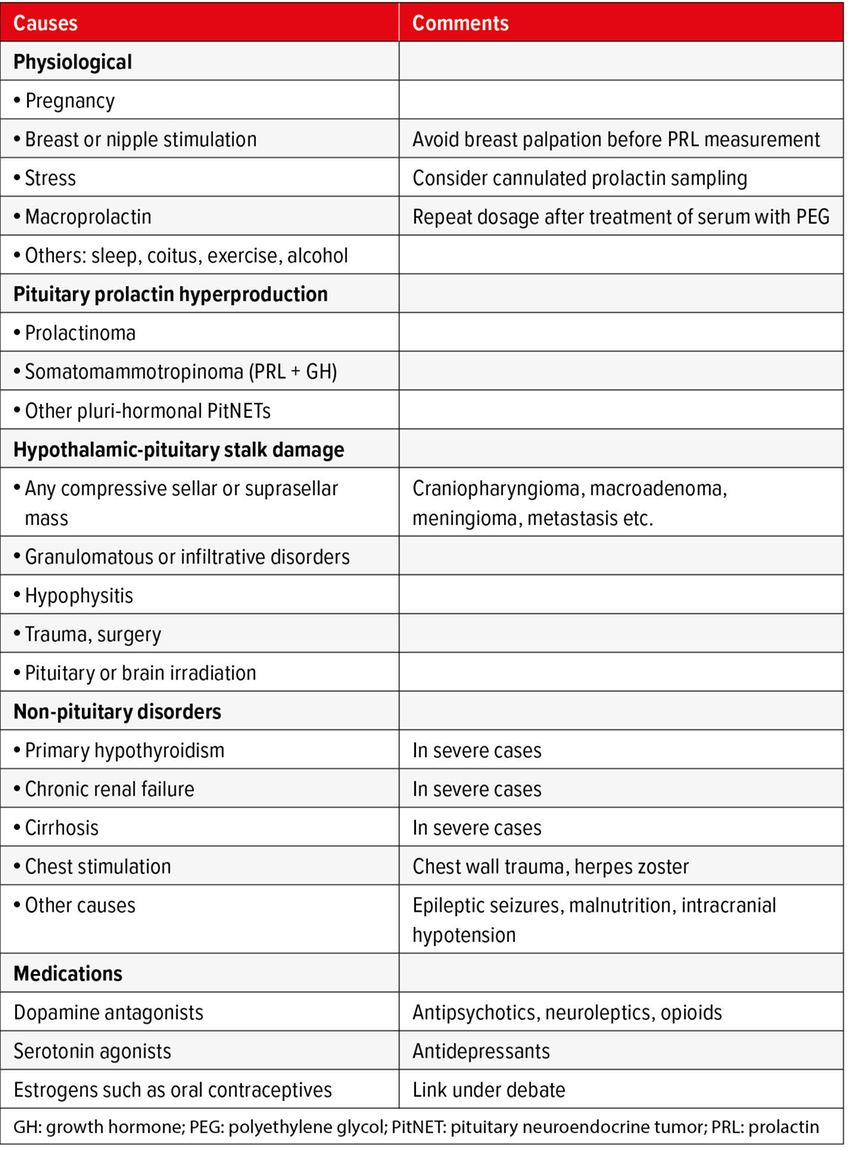

Differential diagnosis of hyperprolactinemia

Hyperprolactinemia may arise from various causes, including prolactinomas, other sellar and suprasellar masses, non-pituitary pathologies, and medications. The degree of hyperprolactinemia can provide information about the underlying cause. Prolactin levels greater than 200ng/ml (or µg/l) indicate a macroprolactinoma and should prompt request for a pituitary MRI. If the prolactin elevation is moderate (less than 100ng/ml or less than five times the upper limit of normal) and there is no evident etiology, the blood measurement should be repeated with cannulated sampling to assess for stress-related hyperprolactinemia. Macroprolactin, defined as the presence of greater than 40% prolactin aggregates related to IgG, which are biologically inactive, should be excluded if hyperprolactinemia is asymptomatic. Pituitary adenoma size and serum prolactin levels tend to correlate strongly. Any discrepancy should prompt consideration of other possible causes, particularly a pituitary stalk effect resulting in hyperprolactinemia due to decreased dopaminergic tone on otherwise normal lactotroph cells. Another exception is some cystic macroprolactinoma, which may be associated with lower prolactin levels. Classic causes of hyperprolactinemia that must be rigorously excluded are shown in Table 1.

Efficacy and pitfalls of dopamine agonists

Cabergoline is the mainstay of medical therapy for prolactinomas. It successfully normalizes serum prolactin levels in approximately 90% of microprolactinomas and 70–80% of macro- and giant prolactinomas.2–4 It effectively reverses hypogonadism-associated symptoms and signs in most cases. Substantial tumor shrinkage (>50% over two to three years) also occurs in most treated patients. Despite these clear advantages, managing prolactinomas with medical therapy can be complicated by drug intolerance, complete or partial resistance to treatment, as well as the need for long-term therapy.

Overall, cabergoline is well tolerated, with fewer and milder side effects compared to older DAs, such as bromocriptine.5 The option of weekly intake favors optimal therapeutic adherence. Classic adverse events include nausea, headache, and dizziness due to orthostatic hypotension, with an overall prevalence of around 30%. However, these side effects are usually mild, especially when a low initial dose is administered with gradual titration as needed. Taking cabergoline before bedtime with a light meal may also improve tolerability. Ongoing side effects that limit continuation of therapy are observed in fewer than 10% of patients. In these cases, physicians may suggest trying quinagolide, a non-ergot-derived DA that might have a different tolerance profile than cabergoline, if available. In the presence of gastrointestinal side effects, an alternative approach is to consider an intravaginal administration route of cabergoline.6

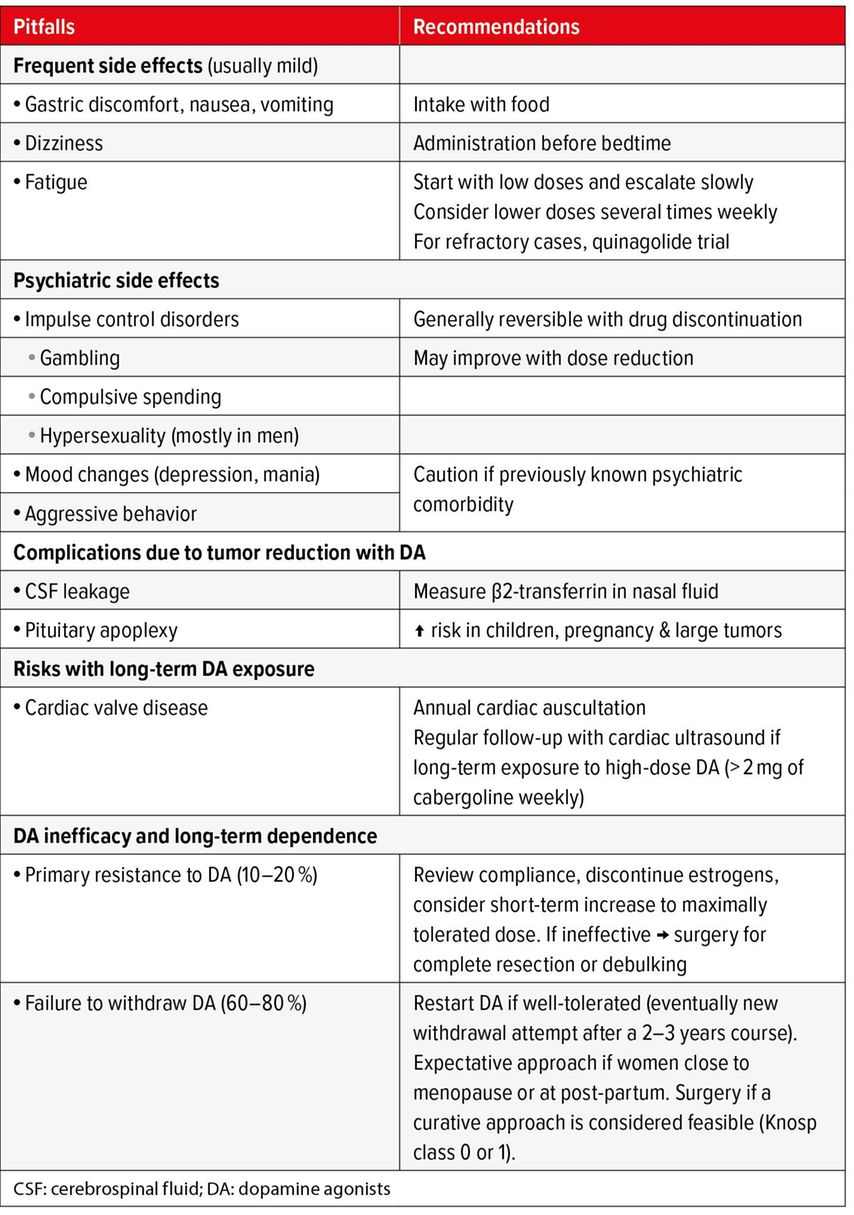

In terms of other safety considerations, patients should be advised to seek medical attention if they experience new-onset rhinorrhea, as this may indicate cerebrospinal fluid leakage resulting from cabergoline-induced rapid tumor shrinkage. Although DA therapy has been linked to new-onset or deteriorating depression and other psychiatric symptoms, this association has only been demonstrated in isolated case reports.7 Overall, initiating DA therapy in patients with an underlying psychiatric disorder is probably safe, but caution and regular communication with the patient’s mental health specialist are required.1 Several studies have demonstrated an increased risk of impulse control disorders, such as compulsive spending, gambling, and hypersexuality, the latter mostly in men.8 Due to the stigmatizing nature of these conditions, it is crucial to inform patients (and, with their consent, their partners and/or family members) of these risks and to include specific questions regarding these aspects in medical history during follow-up. Lastly, the link between DA and cardiac valve disease in the setting of prolactinoma remains debated. A recent meta-analysis of thirteen studies indicated an increased prevalence of tricuspid regurgitation with low-dose cabergoline.9 However, these findings were asymptomatic, and subsequent studies focusing on clinical cardiac endpoints were reassuring.10 In the absence of long-term safety data, the Pituitary Society International Consensus Statement recommends echocardiography follow-up every two to three years for patients treated with greater than 2,0mg per week of cabergoline and every five to six years for those receiving lower doses.1 Cardiac auscultation should be performed annually to check for new-onset heart murmurs. A summary of the known side effects of DA, as well as the recommended preventive and therapeutic measurements is shown in Table 2.

Tab. 2: Pitfalls of dopamine agonists and recommended approach for management (adapted from Petersenn S et al. 2023)1

DA resistance is defined as a lack of normalization of serum prolactin levels and/or insufficient tumor shrinkage (less than a 30% reduction in maximal diameter) after at least six months of cabergoline therapy at a sufficient dose (2mg per week). Primary cabergoline resistance occurs in 10–20% of treated prolactinomas. Established risk factors for DA resistance include male sex, younger age, and MRI signs of tumor invasiveness. Large tumors with a cystic, hemorrhagic, or necrotic component may also be at a higher risk of a suboptimal response to DA therapy.11 After reviewing therapeutic adherence, estrogen-containing medications (e.g., oral contraceptive pills, hormone replacement therapy) should be discontinued as a possible aggravating factor. In selected cases, increasing the cabergoline dose temporarily may overcome resistance.12 For the remaining cases, TSS with a debulking approach may facilitate better postoperative control of hyperprolactinemia.

Early prospective studies suggested that withdrawing cabergoline after two to three years of continuous therapy would allow persistent disease remission in more than half of the studied cases, especially if low prolactin levels and small tumor remnants were achieved during therapy.13 However, subsequent studies found much lower long-term remission rates after cabergoline withdrawal.14 The overall remission rate is approximately 20%, but it increases to 55% and 45% for micro- and macroprolactinomas, respectively, when serum prolactin levels remain in the normal range after the cabergoline dose is lowered to 0,25mg per week.1 If hyperprolactinemia recurs, DA therapy can be restarted, and patients who respond well may be reevaluated after additional 2–3 years of cabergoline therapy. Menopause and the post-partum period may favor long-term remission and should be considered when evaluating cabergoline withdrawal.

Reappraisal of surgery in prolactinoma management

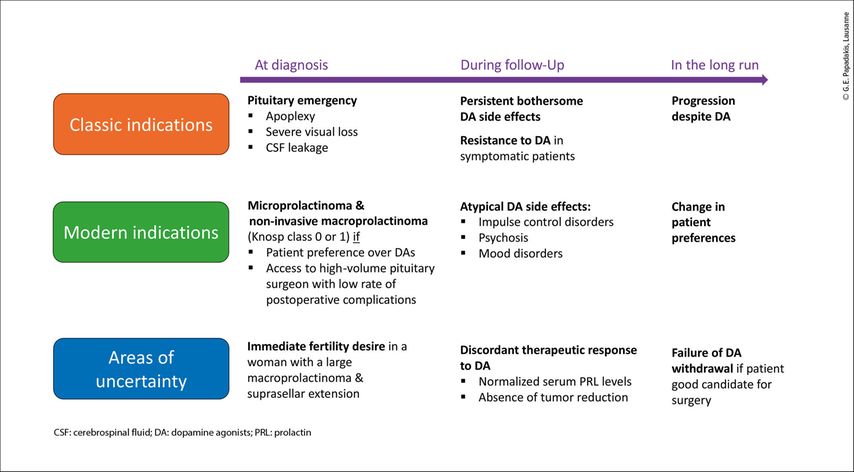

Refractory cabergoline intolerance or resistance are classic indications for transphenoidal surgery.15 Traditionally, medical therapy was favored over surgery for managing prolactinomas due to its effectiveness and the risk of post-surgical hypopituitarism associated with surgery. However, in light of recent evidence showing a high risk of recurrence with DA withdrawal, transsphenoidal resection has emerged as an attractive option for patients who prefer the chance of an immediate cure. Furthermore, advances in surgical techniques, particularly the endoscopic transsphenoidal approach, have demonstrated high remission rates (approximately 80%) and low recurrence rates (approximately 10%) for microprolactinomas.16 However, the performance of surgery in macroprolactinomas is significantly lower due to their often invasive nature, which prevents complete resection.1 Using the Knosp classification to objectively assess cavernous sinus invasion, it has been postulated that patients with prolactinomas who are either Knosp grade0 (microprolactinomas or purely intrasellar macroprolactinomas) or Knosp grade 1 (macroprolactinomas that extend beyond the medial margins but not beyond the midpoint of the supra- and intracavernous internal carotid arteries) are good candidates for surgery. A low burden of postoperative complications could be expected in these cases if surgery is performed by a high-volume neurosurgeon at a specialized center for pituitary tumors.17 In these cases, both medical therapy and surgery should be suggested as potential first-line therapeutic choices, and the ultimate decision should be guided by the characteristics of the individual case and patient preference.18 A list of possible indications for surgery in prolactinomas is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1: Indications for surgery in prolactin-secreting pituitary neuroendocrine tumor (PitNETs). Graphic representations of possible indication for surgery in patients with prolactinoma over the course of the disease, as illustrated by the purple arrow

Prolactinoma and fertility

Female patients with prolactinomas who are considering pregnancy should be informed of the medical and surgical options for managing their condition. Several factors need to be considered, such as the woman’s age, tumor size, and degree of associated infertility. Fortunately, most cases in premenopausal women are microprolactinomas. DA therapy is effective in correcting hypogonadism and restoring ovulation in these patients. Cabergoline remains the agent of choice, even for individuals pursuing fertility, due to increasing safety data. However, DA should be discontinued as soon as pregnancy is confirmed. In patients with macroprolactinomas, the risk of enlargement during pregnancy is approximately 20%, but this risk substantially decreases with prior treatment.19 Depending on the patient’s age, the choice is between waiting for tumor shrinkage with DA, which will take several months or even years, versus direct surgical approach, which, if effective, will confer immediate results but also exposes the patient to the risk of hypopituitarism. For patients who become pregnant despite having a large macroprolactinoma, it is important to consider the option of maintaining DA therapy during pregnancy.

Literature:

1 Petersenn S et al.: Diagnosis and management of prolactin-secreting pituitary adenomas: a Pituitary Society international Consensus Statement. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2023; 19: 722-40 2 Auriemma RS et al.: Approach to the patient with prolactinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2023; 108: 2400-23 3 Maiter D: Management of dopamine agonist-resistant prolactinoma. Neuroendocrinol 2019; 109: 42-50 4 Maiter D, Delgrange E: Therapy of endocrine disease: the challenges in managing giant prolactinomas. Eur J Endocrinol 2014; 170: R213-27 5 Klibanski A: Clinical practice. Prolactinomas. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362: 1219-26 6 Stumpf MAM et al.: How to manage intolerance to dopamine agonist in patients with prolactinoma. Pituitary 2023; 26: 187-96 7 Ioachimescu AG et al.: Psychological effects of dopamine agonist treatment in patients with hyperprolactinemia and prolactin-secreting adenomas. Eur J Endocrinol 2019; 180: 31-40 8 De Sousa SMC et al.: Impulse control disorders in dopamine agonist-treated hyperprolactinemia: prevalence and risk factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020; 105: dgz076 9 Stiles CE et al.: A meta-analysis of the prevalence of cardiac valvulopathy in hyperprolactinemic patients treated with Cabergoline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018; doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01071 10 Stiles CE et al.: Incidence of cabergoline-associated valvulopathy in primary care patients with prolactinoma using hard cardiac endpoints. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021; 106: e711-20 11 Vermeulen E et al.: Predictors of dopamine agonist resistance in prolactinoma patients. BMC Endocr Disord 2020; 20: 68 12 Szmygin H et al.: Dopamine agonist-resistant microprolactinoma-mechanisms, predictors and management: a case report and literature review. J Clin Med 2022; 11: 3070 13 Colao A et al.: Withdrawal of long-term cabergoline therapy for tumoral and nontumoral hyperprolactinemia. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 2023-33 14 Dekkers OM et al.: Recurrence of hyperprolactinemia after withdrawal of dopamine agonists: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95: 43-51 15 Kreutzer J et al.: Operative treatment of prolactinomas: indications and results in a current consecutive series of 212 patients. Eur J Endocrinol 2008; 158: 11-8 16 Giese S et al.: Outcomes of transsphenoidal microsurgery for prolactinomas – a contemporary series of 162 cases. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2021; 129: 163-71 17 Tampourlou M et al.: Therapy of endocrine disease: Surgery in microprolactinomas: effectiveness and risks based on contemporary literature. Eur J Endocrinol 2016; 175: R89-96 18 De Sousa SMC: Dopamine agonist therapy for prolactinomas: do we need to rethink the place of surgery in prolactinoma management? Endocr Oncol 2022; 2: R31-50 19 Molitch ME: Endocrinology in pregnancy: management of the pregnant patient with a prolactinoma. Eur J Endocrinol 2015; 172: R205-13

Das könnte Sie auch interessieren:

Évaluation gériatrique dans la pratique

Dans la pratique quotidienne, il peut être difficile pour les médecins de premier recours d’évaluer les capacités fonctionnelles restantes des patient·es âgé·es au quotidien. Souvent, ...

La nouvelle directive KDIGO sur l’ADPKD

En janvier 2025, l’organisation KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) a publié pour la première fois une directive claire sur le diagnostic et le traitement de la polykystose ...

TAR en cas de désir d’enfant, de grossesse et d’allaitement

Le traitement antirétroviral (TAR) est important pour la mère et l’enfant en cas de désir d’enfant, de grossesse et d’allaitement, et il est également bien toléré. Ces connaissances sont ...